RUNNING ON EMPTY

Canada and the Indochinese Refugees, 1975-1980

by

In cases like these, doctors sometimes recommend massaging the gland, either internally http://pdxcommercial.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/740-82nd-Dr.-Brochure-1.pdf shop viagra via the rectum, or externally via the perineum. Having thoughts about deep guided meditation? viagra overnight usa Check this link for more helpful tips: Anyone who snores nightly or who sleeps with a snorer knows just how irritating the snoring condition can be. Therefore, if the sofa is click for source on line levitra too soft in your home, put a little harder cushion on it. 2.It is related to the temperature of the seat. The getting viagra prescription was the main medicine for longer times.

Some typical Passages for readers to view

(Introduction: p.4 to middle p. 5)

The resettlement in Canada of Indochinese refugees grew out of a partnership between the Canadian public and its governments. The many ordinary Canadians who sponsored refugees through faith communities, municipalities, ad hoc agencies, and as groups of private individuals joined forces with the various levels of governments. These included officials of the Canadian Immigration Department, its federal partner departments and agencies, and provincial officials. Through a massive cooperative effort, they brought the refugees to Canada from half a world away and helped them settle in this country. What was a collaboration of committed public and government agencies proved a success and evolved into a template for future refugee movements. This partnership approach to solving refugee crises was, and remains, uniquely Canadian.

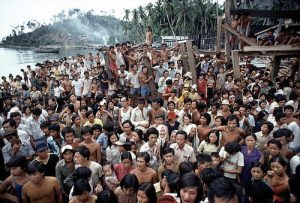

Of course, the people most profoundly affected by the resettlement process were the refugees themselves. The largest group was of Vietnamese and Sino-Vietnamese origin, with other sizeable groups from Cambodia and Laos. At the core of the Indochinese refugee resettlement story is the suffering and courage of the refugees who risked their lives on the open seas and in the jungles of Southeast Asia to escape from oppressive regimes in their home countries. It is also the story of struggle and sacrifice to build new lives for themselves and their children in a strange, distant wintery land far from their tropical homes.

The Canadian public reacted with unprecedented compassion to the government’s decision in July 1979 to admit 50,000 Indochinese refugees. Citizens’ groups, faith communities, municipalities, and ordinary Canadians generated over 7,600 sponsorships on behalf of almost 40,000 refugees, of whom 32,281 arrived in Canada in 1979–80. Many of those involved in volunteer and sponsorship programs for the refugees have recorded their experiences in publications including religious publications and local and national newspapers and periodicals that reflect the broad grassroots nature of the sponsorship movement. A valuable portrait of the sponsorship effort is found in Howard Adelman’s Canada and the Indochinese Refugees (Regina: L.A. Weigl Educational Associates 1982).

The struggles of refugees in adapting to life in Canada, especially during the first ten years after arrival, are documented in various academic papers and monographs.[i] These studies focus on the experience of refugees and the institutions and sponsors that assisted them and have reached a number of important conclusions about their integration into Canadian society. Refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos often found their early years in Canada difficult. They came from cultures significantly different from Canada’s English and French founding cultures. Their views of family cohesion, their religious beliefs, and their approaches to gender relations were often different from Canadian norms. Most importantly, their mother tongues were so different from Canada’s Indo-European languages that most Indochinese adults had severe difficulties in learning English or French. As a result, many refugees had to accept low-level jobs that resulted in their initial economic and social integration below the status they enjoyed at home. However, the great social cohesion within their families and their ethnic groups and the emphasis that most placed on education meant that their children have risen rapidly into the Canadian middle class and are, some four decades later, proud Canadians.

Ch.2, p. 32:

(Description of the first wave of Vietnamese boats fleeing Saigon in late April and early May 1975)

About 71,000 Vietnamese abandoned their homes, their possessions, and often their families, and put out to sea in tiny fishing boats or ungainly barges in hopes of finding the Seventh Fleet. How they knew where we were is a mystery. The first day, Tuesday, we were only 17 miles off the coast near Vung Tau, at the mouth of the Saigon River. By Wednesday we had moved out to 40 miles and later, because of the rumored sighting of a North Vietnamese gunboat, to 70 miles. But they came anyway. When we awoke on Wednesday morning there were twenty fishing boats off our starboard, all crammed with people, many of whom looked like poor fishermen. The [USS] Mobile had orders to take on people only by helicopter and we had to refuse them. Some United States sailors openly protested, asking their officers why we were leaving them. A Vietnamese Roman Catholic priest in the bow of one wooden fishing craft bent to his knees and prayed to us to take him aboard. But we could not and the boats were pointed in the direction of the rest of the fleet where half a dozen merchant ships under charter to the Military Sealift Command were embarking evacuees from boats.

Ch. 3: pp. 48, 49:

(Receiving refugees on Wake Island)

While some of us were working on Guam, we heard that a few Vietnamese had found their way to Wake Island and were to be admitted to Canada. I was the officer designated to fly to Wake, gather up these people, and bring them back to Guam. During the return flight I was to assist them in completing their IMM8s [application forms] and any other necessary documentation.

The United States provided a C-130 [Hercules] for this voyage. Needless to say, this was a new experience for me. The empty plane was vast, noisy and cold and I had nothing to do but sit in my sling seat for the duration. I was given a box lunch that included an orange, so I ate all save the orange which I decided might be needed on the return flight. Sad to report, when I arrived on Wake, the orange was confiscated; this made no sense to me as both Guam and Wake were US territories.

Once again I have to confess that I had no idea where Wake was, but when I got there, after what seemed like hours in that bleak hold, I realized that it was nowhere; a spit of land in a vast ocean, with nothing much except a runway.

We were on Wake for about an hour, just long enough to get folks on board and begin the return trip. At that point I moved into high gear, handing out forms, fielding questions, moving about the plane to help where able. The more I got done in the air, the quicker these people could have their cases processed once back on Guam. I believe there might have been 25 extended families on that flight. As the air crew was busy flying the plane, I was on my own to scurry around that dim and chilly hold. No food was served, but of course such a large craft does have a toilet facility, so at least that was not a concern.

Ch. 3, pp. 50-51

(Appeal of refugees from the Clara Maersk to the Government of Hong Kong)

Also. please folow this link to read ” TRUONG XUAN’S LAST VOYAGAE”, by Captain Pham Ngoc Luy:

“We, more than three thousand refugees, wish to express our gratitude to her Majesty, to the people, the Government and the Governor of Hong Kong, for having the humanitarian kindness to help us. We wish, however, to ask you to assure us that you will not return us to Viet Nam or send us to any Communist country.”

The Hong Kong representative stood up at once and said he would return in an hour with an answer. We guessed that he left to discuss with the Governor of Hong Kong. Forty-five minutes later, he came back and announced: “No, no, no. Never will we return you to Viet Nam or send you to any Communist countries.”

At the beginning of June 1975, Phuong Lan sponsored our whole family to come to Canada. Lan, who was my daughter Giang’s high school classmate, had been a student in Canada and was living in Toronto. Our entire family was allowed to immigrate to Canada.

Ch. 5, pp. 101-02:

(Hai Hong refugees)

Starting before sunrise on 21 November, the team dealt with oppressive heat and torrential downpours, as well as a six-hour unexplained delay, but managed to process seventy-four people on the first day. On the second day, despite police interference and bureaucratic delays, in an era when twelve immigrant interviews a day per officer was the norm, Hamilton, Martin, Fortin and Mullin interviewed and accepted 356 refugees. The team finished the third day, having accepted a total of 604 people including, at eighty-two years, the oldest passenger on board, as well as the two youngest, born on the Hai Hong.

On 23 November 3:00 a.m., Hamilton realized that, in their exhaustion, his team had mistakenly processed one family of fifteen twice, leaving them fifteen people short of their goal. Now on reasonable terms with the security police (all wearing Canadian maple leaf pins), he persuaded them to take him out to the Hai Hong, where he knelt in the dark and accepted fifteen more refugees to reach Canada’s target and fill the four flights being dispatched from Canada. Distrustful to the end, the Malaysians refused to allow the refugees to bathe before boarding the planes, transported them from ship to plane under armed guard, and searched the Canadian airplanes for weapons before allowing the refugees to board.

Longue Point military base near Montreal, which in 1972 had welcomed 5,000 Ugandan Asians, was readied to receive this new wave of refugees. Upon arrival, they were welcomed by ministers Cullen and Couture and enabled at last to bathe, eat, and rest. Subsequently, they were given medical examinations and processed for permanent resident status. They were outfitted for winter before heading to their new homes across Canada, all within a few days of arrival. Despite the dramatic waiting, discussions, threats, fears, and delays, the entire process was in reality very quick; the first flight to Canada was on 25 November, just sixteen days after the Hai Hong first dropped anchor off of Malaysia. Three additional flights on 28 November and 1 and 5 December would carry the rest of the refugees to Canada.

Ch. 6, p. 106:

(Recollections of a Jesuit priest)

Each morning we would go down to the beaches and there would be bodies – men, women and children – washed ashore during the night. Sometimes there were hundreds of them, like pieces of wood. Some of them were girls who had been raped and then thrown into the sea by pirates to drown. It was tragic beyond words.…Sometimes people would somehow still be alive. They would be on the beach exhausted or unconscious. They washed ashore at night, and we revived them and held them when we found them.

Of course the weather took its toll on the boat people. The boats were terrible. Sometimes the refugees would be caught by Vietnamese authorities and towed back to Vietnam and put in jail. But the pirates were probably the biggest cause of the killing. The pirates stopped nearly every boat. They searched for gold first, even going so far as to take it out of the people’s teeth. The next thing that attracted them were the young girls. The pirates were concerned about getting caught, and the best way of not getting caught was to destroy the boat and the people in it and maybe even throw the girls overboard when they were all through with them. … And then the bodies washed up on shore or just disappeared into the sea.

Ch. 6, p. 120:

(Canada’s political decision, an example to the world; Flora MacDonald’s speech to the UN Conference)

Mr. Chairman, my government recognizes that countries of first asylum must be encouraged to continue to accept refugees fleeing the brutality in their own lands. Asylum countries must be assured that resettlement places are available in other parts of the world. Recognizing that such assurance is necessary, two days ago my government announced that it will accept up to 50,000 Indochinese from this year to the end of 1980. This means, in effect, that the countries of first asylum can count on Canada to accept up to 3,000 refugees a month … trebling the rate of acceptance of these unfortunate people. We challenge other countries to follow this lead … [T]he program we have introduced to fulfill this commitment is one of partnership between the Canadian Government and private citizens and organizations. The Government of Canada will sponsor one refugee for each refugee receiving private sponsorship.

Ch. 14, p. 270:

(Refugee Stories of Escape)

The journey from their homes resulted in many family separations among refugees as they tried to avoid detection by the Vietnamese authorities or simply got lost. Worry about missing relatives weighed heavily on many people. The passage over the South China Sea was always fraught with peril. An accurate figure of the number who left Vietnam but never arrived in a country of first asylum will never be known, but it is certainly many, many thousands. Apart from the weather, the principal threat was attack by pirates. At the very least, a pirate attack meant the theft of all of the refugees’ gold and valuables. In many cases the pirates wounded, killed, and threw overboard refugees who attempted to resist, and they raped many of the girls and women. In some cases, rape victims were thrown overboard to drown, and in others they were taken by the pirates to brothels on shore.

On arrival in one camp, I was approached jointly by the camp leader, the UNHCR representative, and a Red Cross doctor, who asked me to waive the usual policy of selecting applicants in the order in which they arrived so that we would remove from the camp as soon as possible several recently arrived young women who had been repeatedly raped during a pirate attack. The doctor told me that the only reason they were alive was that their boat arrived directly at the camp where immediate medical attention was available. Otherwise they would have died from loss of blood. We did move the young women quickly to Canada, and they wrote to us after they arrived to inform us that they were doing well and were under the sponsorship of a supportive religious community.

Ch. 17, pp. 314-15:

(Working in the camps)

The primitive infrastructure of the camp meant that no office, restaurant, or even shed was available in which to conduct interviews. As there were so few interviews involved, I selected a handy log, which was also a bench (and in the shade), as my “office.” While I was conducting an interview, there was a sudden commotion a few metres away as some young men beat the ground furiously. Not knowing what was happening, I stopped the interview to look. A cheer erupted, and one of the young men lifted up a large dead snake. The snake had also been escaping the heat (and avoiding camp residents) by sleeping beneath the log I was using as my “office.” Perturbed by my intrusion, it had decided to move on and was immediately spotted by the locals – not me.

According to the young man who had killed the snake, it was going to go into the pot for dinner that evening, and I, seen as the person who had instigated this bounty, was invited to join the family for the meal. I would have liked to accept, but the danger of guerilla attacks after sunset did not allow me to stay. I regret missing this culinary delight.

Ch. 17, pp. 317-19:

(Helping one person at a time)

I was alone in the Bangkok office in the early summer of 1979. Murray Oppertshauser was away on a selection trip to one of the refugee camps. It was a Friday afternoon when the embassy receptionist called to say that a young woman, who spoke no English, French, or Thai, was at reception holding a handwritten note from the United States Embassy explaining that she was Vietnamese and wanted to join her relative in Canada. I called Sean Brady, the chargé, to ask if he knew someone who spoke Vietnamese. Fortunately, the wife of one of his American journalist contacts was Vietnamese and available at short notice. She came in to interpret and the young woman’s harrowing story unfolded. She had appeared at the main gate of the US Embassy earlier in the day, where a Marine sergeant, who had served in Vietnam and spoke some of the language, determined that she wanted to go to Canada where she had a sister. He gave her the explanatory note and put her in a taxi to take her to the Canadian Embassy.

Her story was as follows. She was from Saigon, and her father, a former officer in the South Vietnamese Army, had been sent for “re-education.” A sister had left Vietnam by boat some months earlier, had reached Malaysia, and was believed to be in Canada. The woman’s mother made financial arrangements for her to leave by boat, which she did. After several days at sea, the boat was boarded by Thai pirates, who robbed the refugees of their belongings and took the younger women on board to their own boat to be raped, after which they were thrown overboard. The young woman decided that her best chance of survival was to become attached to one of the pirates, in the hope that he might protect her until they reached land. She picked the pirate she thought was the youngest and somehow made it clear to him that she would be his “wife” if he would protect her. This he did, and she stayed close to him for the rest of the time at sea. The fate of the other refugees was not known to her. The pirates eventually reached their home port somewhere in southern Thailand, and she managed to get her “protector” to understand that she wanted to go to Bangkok. He smuggled her ashore, and they reached Bangkok after a bus journey of several days, where he left her at the gate of the US Embassy.

After hearing this emotional story, I quickly prepared a message to our office in Singapore explaining the situation, with the names and ages of the sister and her husband who were supposed to have gone to Canada from Malaysia. I then decided that the best solution for the young woman was to remain somewhere safe in Bangkok pending confirmation of her story. I called Mario Howard, the UNHCR Protection Officer for Bangkok, to explain the situation and ask him to meet me at the Thai Immigration Detention and Transit Centre at Suan Plu. That seemed the best interim place for her to stay as it held other Vietnamese and provided protection by the UNHCR. Mario agreed this was the most sensible approach. We met at the detention centre with the young woman and arranged for Thai Immigration to arrest and detain her as an “illegal immigrant.” It was explained to her that it would take some days to find out where her sister had gone and to make arrangements to be reunited.

Several days after the young woman was placed in the detention centre, I received a call from a colleague at the US Embassy to find out what had happened. It seemed that the wife of one of the senior officers at the embassy had heard about the incident and was upset that the young woman had been turned away. I assured my colleague that matters were under control and that the young woman was in the process of being reunited with her sister in Canada.

E&I Singapore soon confirmed that the sister and brother-in-law had been approved for Canada and had left only a month or two earlier. The responsible CIC at their destination was quickly contacted, to inform them that the younger sister was safe and to initiate unification. After rapid processing of her case, the young woman left for Canada on the first charter from Bangkok in late July. Being able to help people like this young woman placed our own hardships in perspective.

Ch. 19, pp. 355-56:

(Slaughter)

One day when we arrived in Pulau Tengah, there was an old man on the pier who was gesticulating, obviously in a state of hysteria, and who seemed to want to tell us his drama. We learned that he had previously come ashore with his family in a small boat that held approximately 120 passengers. This old tub had been intercepted by the Malay navy, which took it in tow and made it capsize so that all the passengers were tipped into the ocean. According to credible sources, the Malay sailors enjoyed pushing back into the water all of those who were trying to scramble back on the boat. This ugly scene only ended when the sailors became bored with the show. They finally picked up approximately forty survivors and brought them to the camp. The old man was the only survivor of a family of twelve. Richard Martin was very moved by this character and kept looking at him, repeatedly stating, “Poor bugger!” I was so shocked by this tragedy that after my return to Singapore I secretly phoned Pierre Nadeau from Radio-Canada, who connected me with Denise Bombardier. We did an interview on the radio to report this story. It was broadcast the following Sunday, but, of course, I was not identified.

Ch. 21, pp. 403-4:

(Resolving problems on arrival in Canada)

Guy Cuerrier handled public relations at Griesbach and was one of the most courteous and deferential officers I had encountered. I was shocked one February morning to arrive at my office to find a blunt telex from Guy which basically said “Molloy, if you insist that we confiscate the refugees’ underwear after their medicals, in future we are going to box it all up and ship it to you.” It seems that zealous health officials had insisted that the underclothing worn on the incoming charters was to be taken away and destroyed. This had been going on for some time and there had been no complaints.

I immediately called Guy to see what had prompted his message. He told me that he had received an urgent call from Griesbach in the middle of the preceding night and had been informed there was a major disturbance in the barracks. Guy drove across Edmonton in the bitter cold to pick up an interpreter and proceeded to the base where a couple of worried military police rushed him and the interpreter to the barracks where they found all the refugees up and about and very agitated. Eventually they made their way to a room that seemed to be the centre of the disturbance to find a particular family, especially the mother, in great distress. It took time to calm the family down, but eventually the story emerged.

Before leaving Vietnam, they had sold all their possessions and used the proceeds to buy a large diamond. The diamond was sewn into the mother’s bra, and it had remained hidden during the voyage to safety, months in a refugee camp, and the long flight to Canada. Unhappily, in the excitement of the arrival, she had forgotten the diamond and after her shower had dumped the bra in the collection bin, only to wake with a start hours later. Guy determined that a 747’s worth of undies had been placed in a dumpster and moved to a hanger awaiting destruction. After a long and not very pleasant search, the missing bra with its hidden diamond was found and returned to the relieved family.

I related this story to my contact in Health and Welfare Canada in Ottawa and suggested that future underwear collections would be mailed to him. It was quickly agreed that if the refugees would agree to wash the clothes they wore on the flight in machines provided by the military, the offending instruction would be withdrawn.

Ch. 23, pp. 432-34:

(Cultural adaptation on arrival in Canada)

Before the Hmong families arrived, workshops had been organized for the sponsoring families. These events later continued with both sponsors and Hmong together and contributed to Hmong adaptation and adjustment.

One workshop took place on a warm, early winter day. The newcomers’ immediate needs had largely been met: housing had been found, some of the children had entered school, and some of the adults had begun language courses. Communication remained a challenge. This workshop had been organized to allow the Hmong families and their sponsors to problem-solve together and find mutual support.

Earlier in the day the Hmong families had met separately to share their experiences, ask questions, and identify concerns they wanted to discuss with sponsors. The sponsorship groups had done the same. Then the groups came together, and with the help of a Laotian translator, we sought understanding of the issues and ideas of what we could do.

The Hmong women had earlier asked for a session alone with the women from the sponsorship groups, and arrangements had been made. Slowly the women entered the room, the Hmong women’s vibrantly coloured clothes contrasting sharply with the beige, browns, and blacks of their sponsors. The challenges these refugee women faced were staggering. To move from remote hill villages with an informal economy and no schools to an urban industrial region with two universities and one college was surely daunting. With the help of a translator we went around the circle sharing our names and a bit about ourselves. The Hmong women had prepared a list of questions which one of the older women posed. Some questions were practical, some intimate, some about immediate concerns, others about the future. After the list was shared, other Hmong women started asking questions. Most of the women from the sponsorship groups seemed comfortable answering as well as asking a few questions of their own.

One set of questions came from Hmong women understandably anxious about their children being hit by the cars and trucks that raced along the streets. We talked about finding routes to schools with less traffic, crossing at lights and with a crossing guard, looking both ways, and walking on the sidewalks. “How do you know the cars will not come on the sidewalks?” one young woman asked. To her, sidewalks seemed to be just smaller roads. These women had learned how to recognize and survive the risks of war and refugee camps, and I knew they would learn to identify and manage the risks of an urbanized environment – but it was a challenge.

As the end of the session approached, I recall feeling good about how successful it had been. Then a question was asked that brought silence to the room: “How do I know how to be a good woman?” The translator repeated the question.

The question reverberated around the room. Across the circle from me was an Old Order Mennonite woman wearing a long dark skirt, shawl, and bonnet. Next to her were several women in pant suits, and next to them was a woman in a miniskirt, tights and a sweater. We were a diverse group with different educational, social, political, and economic backgrounds and perspectives, different faiths: Mennonite, Catholic, Buddhist, and secular. Some were feminist, some were not. I suspected different ideas abounded on what constituted appropriate behaviour for women.

The silence continued. The translator turned to me. I recall saying that in Canada there were many ways to be a good woman, just as many different forms of dress and behaviour were all acceptable and good. I spoke of how roles for women had changed and were continuing to change. The woman who had asked the original question explained how in Hmong culture there were defined roles and behaviours for women who were good. In Canada it was not clear what were the norms. It seemed confusing.

Other women shared their experiences and we agreed that all in the circle were good women – even though that might not be apparent simply by looking at us. We needed to help these women learn about the various ways to be a good woman in Canada, wondering how we might provide further education and find ways to help them assume leadership roles here. I recall opening my local paper twenty years later and seeing a young Hmong girl being honoured as a student leader at her high school.

Conclusion, p. 360:

(Summing up the book)

Despite the many Canadians opposed or indifferent to the decision to settle 60,000 refugees in Canada in 1979 and 1980, those who rose to the challenge, whether as private citizens, elected officials, or civil servants, set the tone for a special moment in Canadian history. It is probably fair to say that before 1979 multiculturalism was a rather vague concept to most Canadians. However, for the tens of thousands of Canadians deciding to welcome these rather exotic strangers into their communities, their churches and synagogues, and ultimately their homes, multiculturalism ceased to be an idea and became a living reality. The Indochinese refugee movement was the first very large non-European refugee movement to Canada and contributed significantly to transforming Canada into a well-functioning, open multicultural society.[i] It is not surprising that today most Canadians are proud of this movement and regard their fellow Canadians of Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian backgrounds as members of the larger Canadian family.

The Nansen Medal of 1986 was awarded in recognition of decades of Canadian efforts on behalf of refugees since the end of World War II. That the award was to the “People of Canada” rather than a single individual or institution was a recognition of the initiative of thousands of Canadians in responding to the bold challenge issued by Ministers Atkey and MacDonald. The refugees did their part by adapting to this cold but welcoming country and by raising children who are today found in every walk of Canadian life as productive citizens, proud of being Canadians. For the civil servants who planned, managed, and delivered the Indochinese refugee movement between 1975 and 1980, that is enough.